Seven Sisters, 2021

Sister Esso; Sister BP; Sister Mobil; Sister Texaco; Sister Gulf; Sister Chevron; Sister Shell: beer tap and various materials and dimensions

In Greek mythology, the Seven Sisters were the seven daughters of the Titan Atlas, they were first transformed into doves and later placed in the sky by Zeus where they were immortalised as the constellation Pleiades.

However, Seven Sisters also stands for the seven leading and invariably Western oil companies that controlled the oil market with up to 85 per cent of the world’s oil reserves, from the 1930s (Achnacarry Agreement 1928) until the founding of OPEC in 1960 and the oil crisis in 1973. Both the ever increasing demand for oil, and the exploitative production contracts that the unofficial oil cartel Seven Sisters negotiated with the financially, technically and politically weaker oil producing countries of the Middle East, meant that these foreign oil companies quickly, within just a few years, became the biggest and most powerful companies in the world, enabling them to determine both the price of oil and the amount produced. Today, among other oil supermajors, four of the Seven Sisters remain: ExxonMobil, Chevron, Royal Dutch Shell and BP.

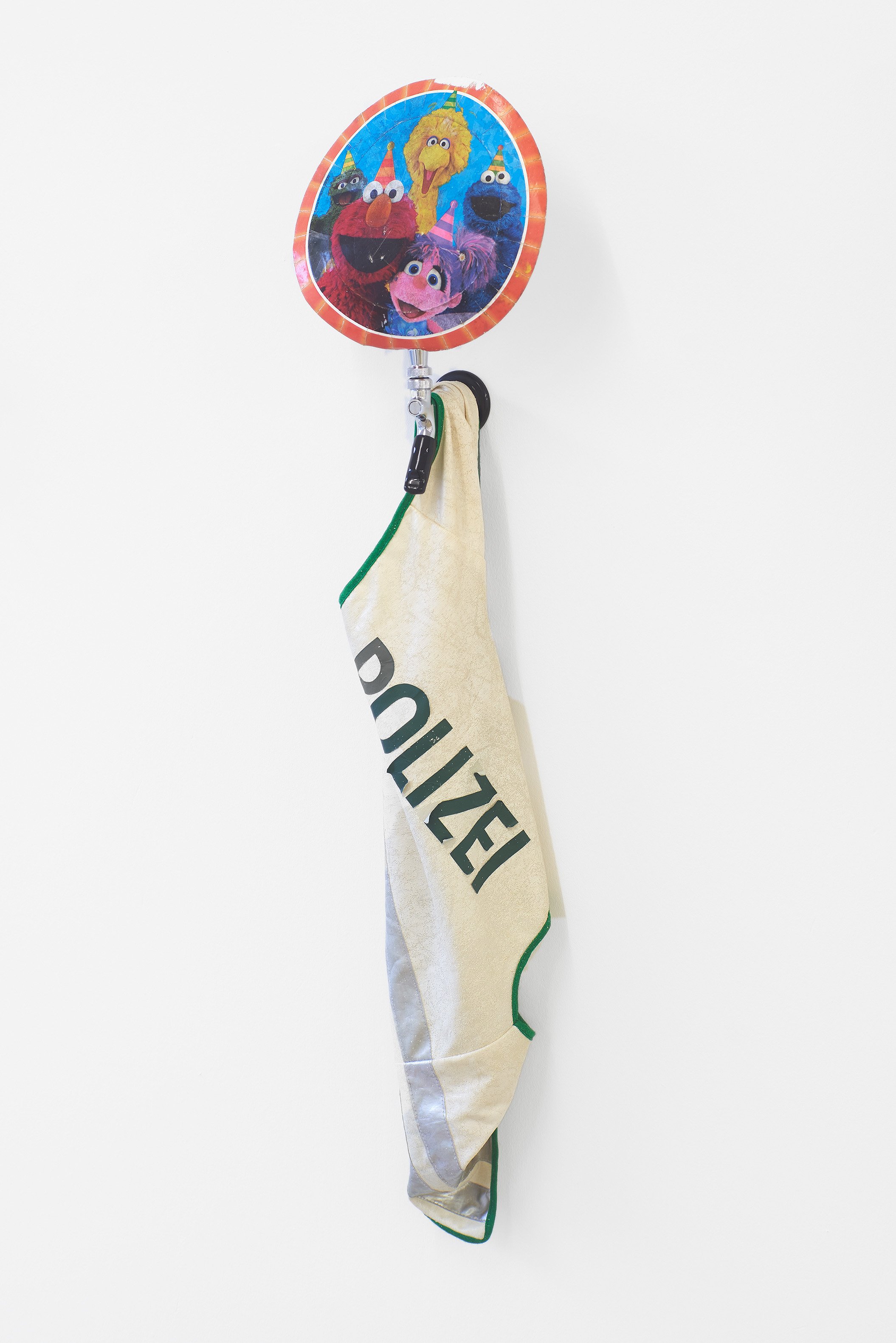

Each of the seven wall objects is named after one of the original seven oil companies: Sister Esso, Sister Shell, Sister BP, Sister Mobil, Sister Chevron, Sister Gulf and Sister Texaco (*1). As a group, the seven objects also bear the collective title Seven Sisters. They each consist of a beer tap, as well as an arrangement of constructed and transformed materials, objects and remnants.

All of the components comprising the ‘Sisters’ come from the collective, equal and equivalent materials that have been extracted by the various sequences of our fossil fuel based reality. After all, fossil fuels are not only those innumerable materials that have penetrated into the smallest aspects of our lives, but they have also intoxicated the human imagination and distorted human knowledge. Today, everything is somehow related to oil; from, for instance, environmental disasters, wars and power regimes – the totalising impact of a global capitalist culture and its systems – to forms of highly compressed energy, compressed time and much of our thoughts and stories. Through the use and intermixing of both symbolic and banal-everyday references, each of the seven sculptures conveys an individual, as well as a multi-layered narrative that involves specific cultural, social, political and historical considerations, while at the same time being contaminated by one another.

The wall sculpture Sister BP is a fragile construction made of a folded aluminium lampion and a glow-in-the-dark plastic star that is suggestive of the Turkish national flag. Sister Gulf comprises a male peacock, which is something that played a pivotal role in both the seduction of Adam and Eve and the prophet Solomon; here it is made of cracked industrial porcelain and mounted on a marble base on which “for to forgive is overrated” is engraved upside down. Sister Shell is comprised of a damaged Nefertiti bust, whose helmet crown has been extended into a solid protuberance by a faded, now lilac-colored, Ikea chair leg. A palm-like tinsel decoration, partly iridescent, partly burnt, shapes Sister Chevron, whose “leaves” conceal a dental crown that looks rather black and gold in color, instead of white and gold. The characters Abby Cadabby, Oscar, the Cookie Monster, Elmo and Big Bird, known in the internationally popular children’s TV series Sesame Street as everybody’s neighbors and friends, gaze back at you invitingly and alertly from a dirty paper plate stretched out to form a sign in Sister Mobil. Meanwhile, a torn waistcoat from a child’s costume that has been casually thrown over the tap legibly displays the inscription “Polizei” (Police). The angular, conical body of Sister Esso, constructed as if improvised, yet sturdy, out of cardboard and masking tape, features a melted, now hardened puddle of transparent plastic, as well as a crown, resembling a turban, which billows and spills out of a pair of boxer shorts bearing the logo “Lucky Brand”. Sister Texaco consists of soft, fragile planar surfaces – a paper bag from the Texan liquor chain Spec’s stained with white paint and a festive white scarf.

The pipes of the taps visually appear to vanish behind the wall (here the Kölnischer Kunstverein), as if they were penetrating further into the building, continuing into its interior and from there into the unknown. At the same time, they return from this illusion of distance and separation and emerge out of the wall as the protagonists of the Seven Sisters, as well as of a popular or political culture. Not without reason, the taps appear as a reference to beer culture, a predominantly male industry, most notably in the echo of the title “Sister”, as well as the black rubber protector draped over the tap opening.

The work Seven Sisters absorbs various aspects of the visible and invisible, of a world shaped by oil exploration, that is, the world as we know it now. We have already reached the moment of ‘peak oil’, the highest point of production, acceleration and extraction through temporary drilling platforms, fracking, pipelines along houses, settlements, boomtowns and culturally valuable sites, tapped by oil giants, oil nomads and consumers. We, in our capitalist modernity of fossil fuels, find ourselves both in a state of historical emergency that cannot be sustained, and on an unknown path.

*1) Esso, formerly Standard Oil of New Jersey; Shell of Royal Dutch Shell; BP, formerly Anglo-Persian Oil Company; Mobil, formerly Standard Oil of New York; Chevron, formerly Standard Oil of California; Gulf Oil, broken up in 1984; Texaco, merged with Chevron.

Photo: Alwin Lay, Selma Gültoprak

Installation view: Kölnischer Kunstverein, 2021